One of my interests is hermeneutics, or the study of meaning-making and interpretation. Hermeneutics arose originally from the study of sacred texts, but has more recently been extended to encompass meaning and understanding in different contexts, and to the interpretation of material other than text. As history also involves interpretation of material and the creation of meaning, the two disciplines overlap. There are further parallels with education and the theories of how people learn, another interest of mine.

This page includes material from a talk given to the Society for One-Place Studies in July 2022 and subsequently published in 'Destinations', the Society journal, in September 2022. It focuses predominantly on the work of Hans-Georg Gadamer and Paul Ricoeur, with Alfred Watkins as a case study.

This page includes material from a talk given to the Society for One-Place Studies in July 2022 and subsequently published in 'Destinations', the Society journal, in September 2022. It focuses predominantly on the work of Hans-Georg Gadamer and Paul Ricoeur, with Alfred Watkins as a case study.

Hans-Georg Gadamer 1900-2002

Paul Ricoeur 1913-2005

Alfred Watkins 1861-1902

Why do we believe that?

When we study our places we gather information from a variety of sources, consider it and use it to form conclusions about our places and the people involved in them. Why do we reach for conclusions we do about our researches? This article will look at some of the things which affect what we believe and how we come to believe things about our places and their people. First however, I’d like to introduce you to Alfred Watkins, who is going to help us illustrate these points.

When I began researching Alfred, I was aware of a number of ‘facts’ relating to his origins. His death certificate indicated that he was 36 when he died in 1902 – he wasn’t. His marriage certificate (1883) indicated that his father was a firebeater called “----- Watkins’. There is no evidence that either the father’s surname or occupation were correct. Alfred’s daughter-in-law said that he came from Wales whilst the 1891 census suggested Cumberland. Both were wrong.

The views of Alfred’s daughter-in-law are particularly interesting It would be easy to assume that she was speaking from knowledge. However she never met him – he died when she was six. All her knowledge of her father-in-law was second hand, probably from family members.

Consider a simple conversation, such as between Alfred’s daughter-in-law and other family members about his origins. Conversations may be thought of as being made up of four aspects:

· thinking

· speaking

· hearing

· understanding

Interpretation occurs at each stage. A consequence of this is that two people may think they agree on something whilst actually having reached totally different conclusions.

Similarly, interpretation also occurs at every stage in the sequence of events which leads to the production of the records we use in our researches. Taking the census for example, the choice and wording of questions was driven by the information the civil service thought it needed to address the issues they thought the country would face in the next ten years – choices at every stage, and that’s before a single form has been completed.

Hermeneutics is the study of the theory and principles of interpretation. It was originally applied to interpretation of sacred texts but more recently this has been extended to cover how people interpret their world within a given social and historical context. In this article we are briefly going to look at four main aspects:

• All data is interpreted

• All research has context – ours and the record’s.

• The same information can lead to different conclusions

• Question everything – then reconstruct

The first aspect is that all data is interpreted. This is based on the work of of Roy Bhaskar (1) who made two main arguments, that there is such a thing as absolute truth, but that all knowledge is interpreted.

Using our example, Alfred either came from Wales or he didn’t. He was either born in 1866 or he wasn’t. His father was either a firebeater or he wasn’t. There is an objectivity here.

However Bhaskar’s second argument states that all the data is interpreted, at all stages of its production. We gather evidence, weigh it and come to a conclusion, in this case about Alfred’s place and date of birth. This conclusion may be accurate, partly correct or wildly wrong.

A consequence of this however is that there is a tension between the objective and the subjective, between what is true and the meaning we attached to things. This should lead to humility and respect in our researches– we don’t know it all, our reconstructions may not be accurate and may be affected in ways we don’t even consider.

The second aspect is that all research has a context. We have already discussed that all data is interpreted. This interpretation doesn’t occur in a vacuum. So when we discover a new piece of information we don’t approach it ‘cold’. There is a context, and that context is what we knew about the individual, family, place, document type and so on before we discovered the new fact.

The name most closely associated with this work is that of Hans-Georg Gadamer (2), and we will meet him again in the next section.

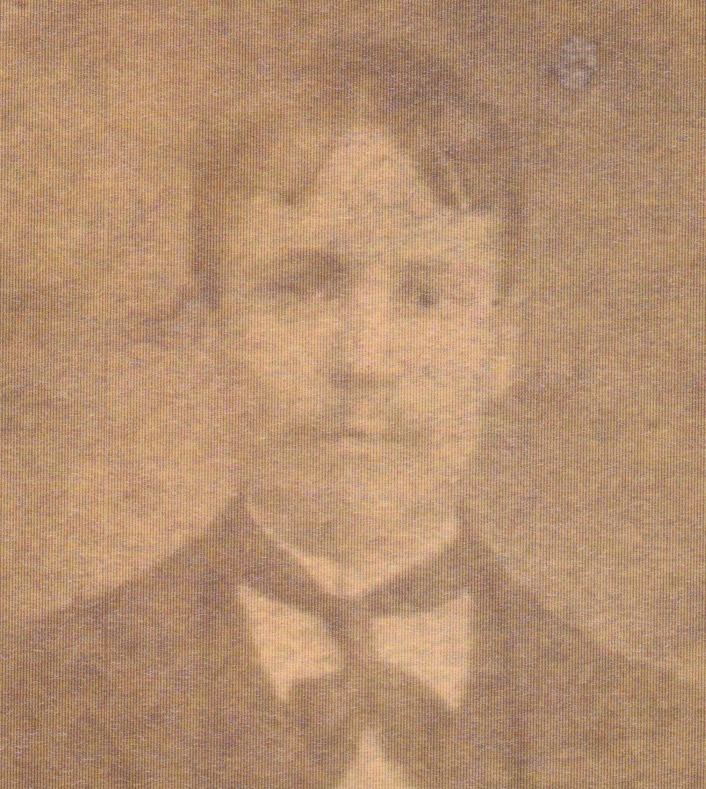

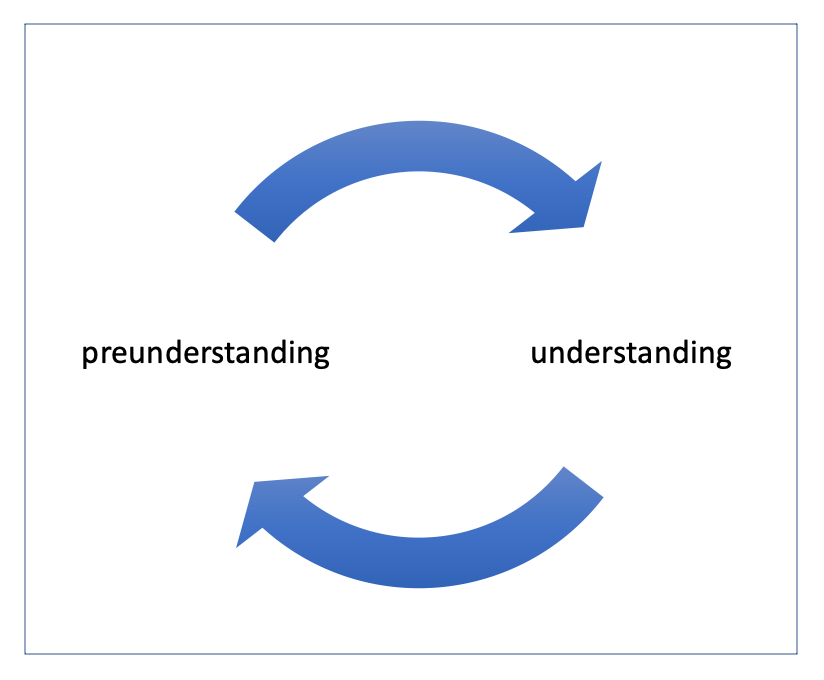

Gadamer pictured the process of interpretation as a circle, in which the ‘whole is what we knew about the topic before starting our next piece of research. The ‘part’ is what we find out as a result of our researches.

The ‘hermeneutic circle’ or the relationship between the new piece of knowledge ‘(the part’) and our understanding of the entire topic in question (‘the whole’).

We interpret the ‘part’ in the context of the ‘whole’, that is to say the new information is interpreted in the light of what we already understood about the topic or question

The new piece of information, the ‘part’, changes the understanding of the ‘whole’, that is our understanding of the topic is different because of our new discovery. Sometimes this is a minor change, sometimes it leads to a fundamental change in perspective, but in any event our understanding is bigger and different to how it was before.

As our understanding has changed, the next piece of research is from a different starting point and the next piece of information is interpreted in that new context. Each changes the other.

Gadamer called this the ‘hermeneutic circle’ but as the situation changes with each cycle it may better be thought of as a spiral. This change in understanding with new information is one reason why revisiting early stages of research can lead to fresh insights. It’s a bit like a jigsaw, it’s easier to put in a piece if you know what the picture is. It’s even easier if there are some pieces already in place to guide you.

So back to Alfred. I had some information, that he came from Wales or Cumberland. Any new information was interpreted in the light of that. This not only led me to a fruitless search in those areas for a while but also inhibited my exploring other options.

Actually though, there are two circles to consider. This second one relates to our overall understanding of the topic, the ‘whole’ in the first circle.

We approach a topic with a preunderstanding of its content. As we consider new information, we do so in the light of that preunderstanding, which is itself altered by the new material.

We have already said we approach a topic with an idea of what it’s about, however basic that idea might be This is known as our ‘preunderstanding’ of the topic. Our preunderstanding tends to colour our approach to an issue – if we approach Latin or secretary hand from the basis that it is difficult, then we may struggle with things which actually are well within our capabilities. They also shape the understanding we ultimately place on something and the meaning we attribute to it.

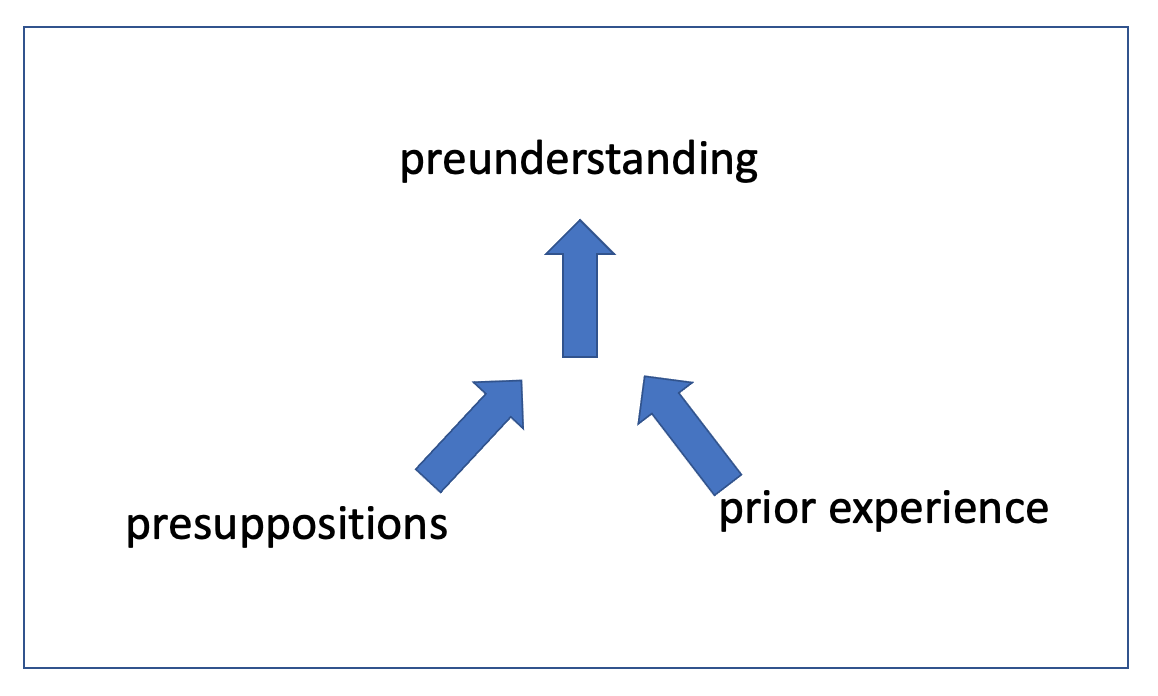

So where do we get our preunderstanding from? Gadamer said that they are a combination of two things.

Our preunderstanding of a topic is formed from our prior experience and our presuppositions.

One of these is our prior experience of the topic in question, which influences how we approach things. The second, our presuppositions, is more subtle and tacit. Broadly speaking, a presupposition is something you assume to be true, particularly something which you must assume is true in order to continue with what you are thinking (3). Two major components of our presuppositions are our personality and our worldview. The latter is the way we understand the world and is governed by our views on humanity, time, the purpose of life, the nature of truth, reality and morality and so forth. Answers to these questions determine our approach to many things, even many which are apparently unconnected.

We all have our worldview. This may be different to that of our ancestors, which may itself differ from that of people around them, or of different cultures or social circumstances.

Applying this to the example of Alfred Watkins, we often assume that there was a stigma associated with illegitimacy in the late 19th century. It is of interest that Alfred didn’t ‘create’ a father for his marriage certificate. He was 210 miles and 21 years from his birth place and date, so would be unlikely to be found out had he done so. Yet he didn’t. We need to be careful in applying our assumptions onto our one-place residents.

Thirdly, since different people have different prior experiences and different worldviews, they may reach different conclusions from the same information. We see this with the contrasting approaches newspapers take to reporting current events. A further layer of complexity is added if the records we are considering come from a different era to our own.

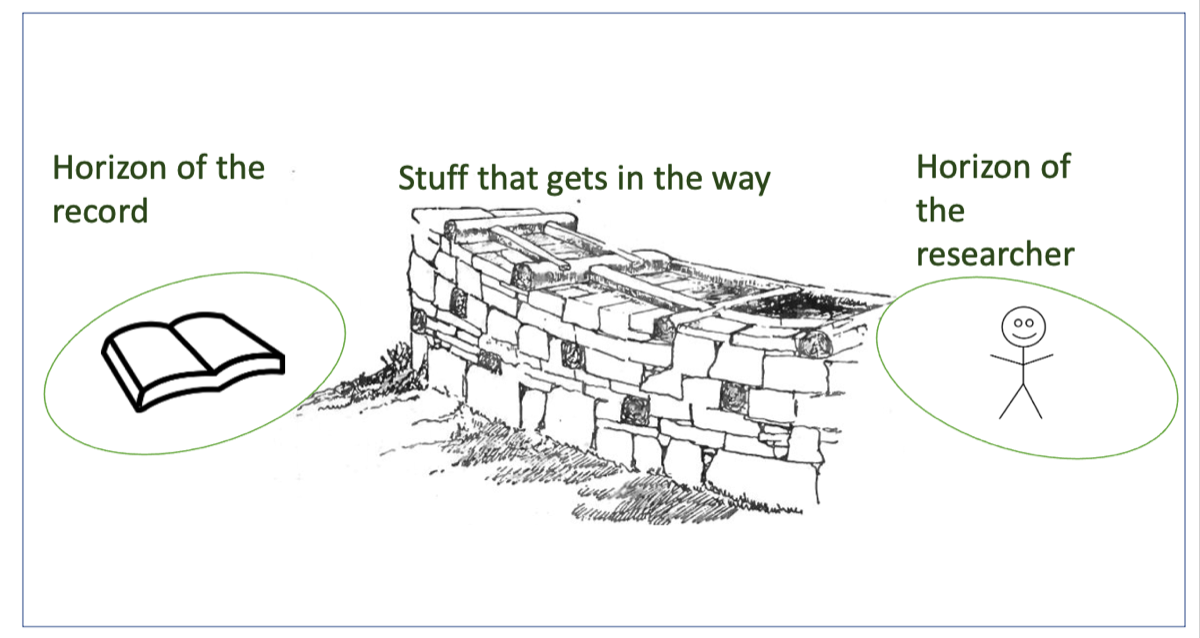

Gadamer recognized this and referred to the ‘two horizons’. One horizon is that of the original record and the sense it made in its original context. The second is that of the researcher, and the sense they make of the record when looking at it today. These rarely overlap exactly (or even, sometimes, at all!) and are kept apart by stuff that gets in the way. This stuff includes lots of things: tradition, presuppositions, culture, worldview, bias, ways of thinking and so on.

Our understanding of the records we study is sometimes affected by the distance and difference of our world from that in which the record was created. ‘Wall’ diagram from S Baring-Gould, “A Book of Dartmoor’ via Wikimedia

We can minimise the understanding gap (or in Gadamer’s terms ‘fuse the horizons’) by considering each part of the diagram in turn.

On the one hand we seek to know everything about the record, why it was made, what were the intentions, constraints, problems behind its production, what was it seeking to achieve and so on. Understanding the original meaning and provenance of our sources helps, as does the background events, culture, societal forces etc. That’s one reason why a One-Place Studies approach can help family history, as well as being interesting for its own sake.

On the other hand we can seek to know ourselves, our biases, how we think, how we respond to difficulties. This overlaps with areas of cognitive psychology. Thirdly we learn from others within learning communities and those who have gone before. Nobody knows it all.

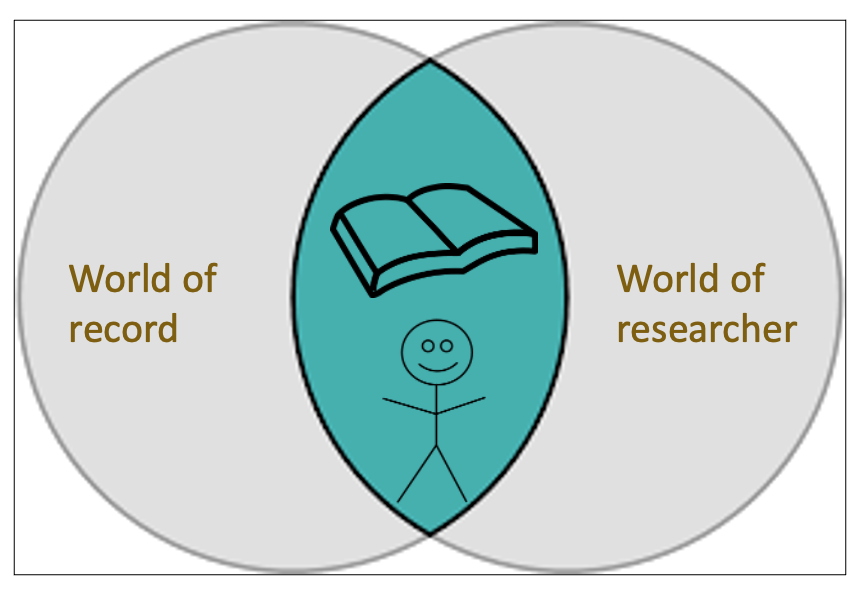

The aim is to achieve a shared understanding between the worlds of the record and the researcher. The more this happens, the more likely that our conclusions reflect what the record is actually telling us. In contrast, if these horizons don’t begin to fuse then our misconception of the record is built into our preunderstanding, which then affects how we approach the next record…

Deeper understanding of our world and that of the records helps increase the degree of overlap between the two worlds and hence the accuracy of our interpretations of the records.

As we understand the records and ourselves better, the area of the overlap between our world and that of the records overlaps, hopefully to an increasing extent. The greater the degree of overlap, the more likely that the conclusions we reach accurately reflect the intended meaning of the records.

One approach to bridging this gap comes from the work of Paul Ricoeur(4). Ricoeur described a two-stage approach to a record or event, which he labelled suspicion and appropriation, or question then reconstruct. In both of these he advocated trying to free ourselves as far as possible from our presumptions and biases and let the record speak on its own terms.

The ‘suspicion’ stage involves questioning everything to do with the record. This involves understanding the provenance of the record itself as discussed above. It goes deeper however:

· what does it mean?

· what alternative meanings are there?

· what are their consequences?

· what do I not know?

· what changes if…

· what difference does it make if…?

In this stage the material is analysed, studied, deconstructed, and deep and alternative meanings sought and weighed. Generally, tear it apart. The idea is that by questioning the evidence in this way we try to free it from our presuppositions, from the baggage we bring to it. The key question here is ‘why do we think that?’ or ‘why do we believe that?’

Having torn it apart, we then put it back together again by building it into our body of knowledge. It then forms the basis for future plans, actions and deductions and generally becomes part of our study.

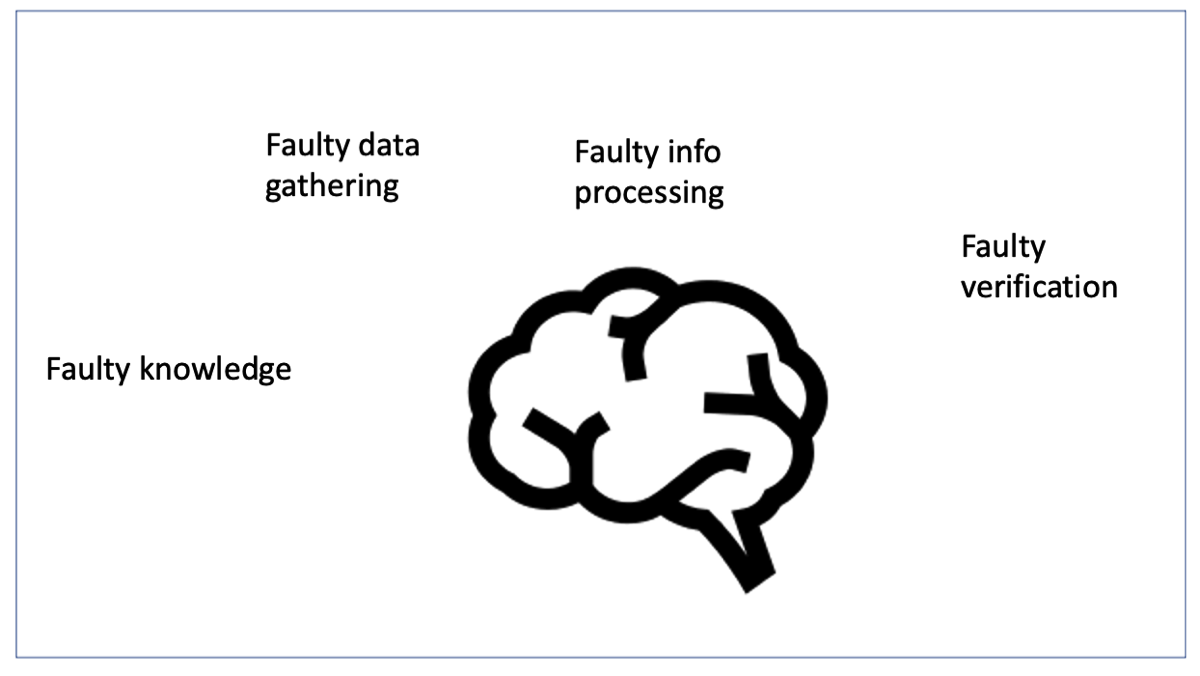

Do we rush to this bit in the excitement of the discovery? Perhaps, sometimes. This is where faulty thinking has a role to play. This is a huge subject by itself but briefly, cognitive errors may be involved at each stage of the thinking process:

Some categories of cognitive biases.

Knowledge: what we do know, knowing what we don’t know, knowing where to find it, knowing how reliable the source is.

Data gathering: the tendency to emphasise data we seek out for ourselves over info given to us

Information processing: jumping to conclusions, fixation errors, availability errors, rules of thumb

Verification: fail to consider all options, confirmation bias, failure to look for what proves you wrong

Most issues with faulty thinking involve information processing and verification, issues with knowledge or data gathering are relatively minor. There are a number of tools which may help here minimize these errors, two of the best known being Kahneman’s ‘Thinking fast and slow’ and de Bono’s ‘Six thinking hats’. These have been applied to genealogy by Sophie Kay(5).

Back to Alfred, who illustrates a number of these principles. Firstly there was insufficient questioning of the reliability of much of my initial information. This was compounded by confirmation bias, with a tendency to discount information which didn’t fit into my prior understanding. There was a presupposition that family information was reliable, whether that was his wife’s recollection of his age or his daughter in law’s understanding of his birthplace. There was a failure to recognise that Alfred’s age, and that of his wife, being recorded inconsistently in a number of documents suggests that documenting (or even knowing) it accurately wasn’t important to them. I didn’t question the sources thoroughly enough. I rushed to build compatible information into our current view. Yes, these were rookie errors made many years ago working with microfilm in the Family Records Centre of the local LDS church. By being so glaring however they illustrate how the theories outlined above can influence our studies in more subtle ways which nevertheless lead us heading off in the wrong direction.

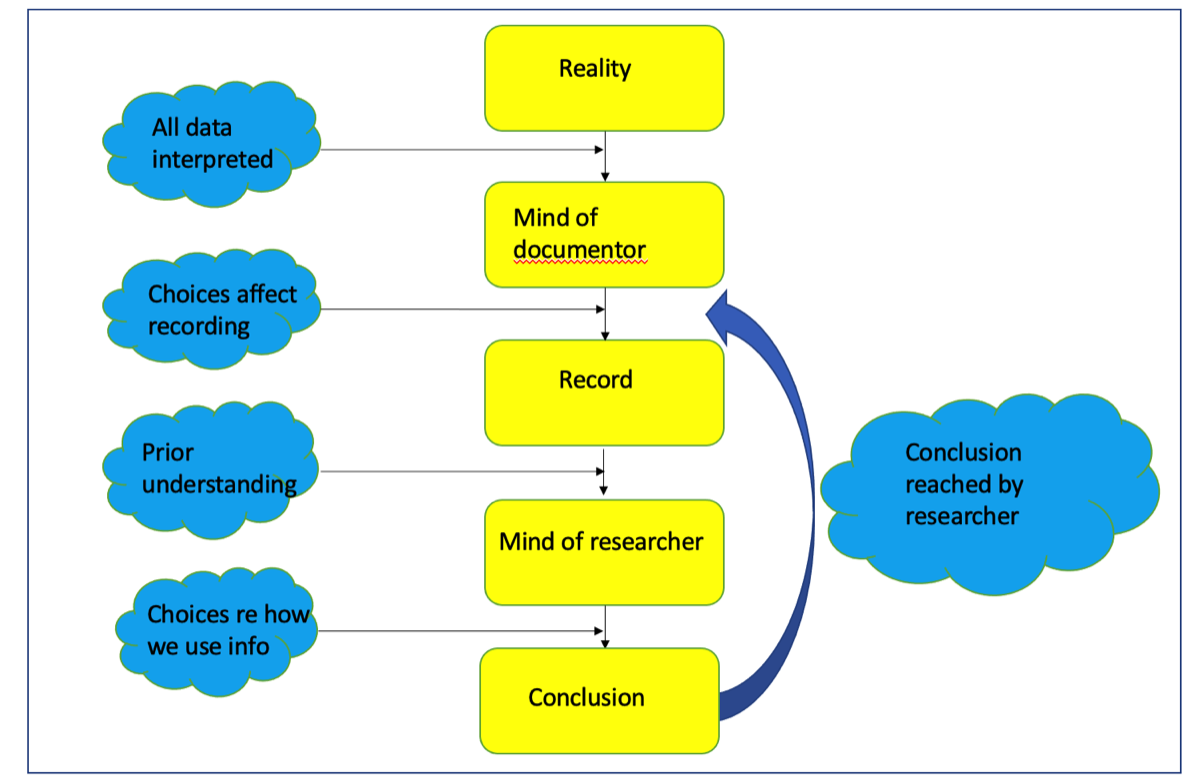

Summary of the interpretation process.

In conclusion:

This article introduces some of the key concepts in hermeneutics or the study of meaning-making and interpretation as summarised in the diagram above.

I have argued that whilst there is such a thing as an absolute truth, in reality all data is interpreted, often at multiple stages in the process of data generation, recording, discovery and analysis. This is known as critical realism. Further, no data occurs in isolation but arises from and is interpreted in a context, and that context affects the interpretation process – what Gadamer called the hermeneutical circle. These contexts are different for the worlds of the record and the interpreter (and different for different records, and different interpreters). Consideration of both these worlds – ours and the records – can lead to a greater degree of shared overlap between them or, in Gadamer’s terms again, the fusing of the horizons. Finally extensive, structured questioning of the data helps us discern its meaning, which is then built into our body of knowledge and understanding, a process Ricoeur described as suspicion and appropriation.

I hope to unpack some of these further in future articles or blog posts. However an understanding of how we form conclusions and why we believe what we do can help researchers avoid some of the pitfalls illustrated by Alfred Watkins.

References:

1. Bhaskar R (1975) ‘A Realist Theory of Science’. Abingdon-on-Thames Routledge. This edition 2008.

2. Hans-Georg Gadamer (1960) Truth and Method. London, Continuum (this edition 2004).

3. Collins COBUILD Advanced English Dictionary (2018) NewYork,, HarperCollins

https://www.collinsdictionary.com/dictionary/english/presupposition accessed 17 August 2022.

4. Ricoeur P. (1969): The Conflict of Interpretations: Essays in Hermeneutics. London, Continuum (this edition 2005).

5. Kay S (2022) ‘6 Thinking Hats for Genealogy’ https://parchmentrustler.com/family-history/six-hats-for-genealogy/. Dr Kay has also spoken about fast and slow thinking in this context.

(Based on a presentation given to the Society of One-Place Studies on July 14 2022. All diagrams are mine unless otherwise stated. With thanks to Helen Shields for constructive comments on the draft article.)